State of Hawaii

Mokuʻāina o Hawaiʻi |

| |

| Nickname(s): The Aloha State |

Motto(s): Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ʻĀina i ka Pono

(“The Life of the Land is Perpetuated in Righteousness”)

Anthem: Hawaiʻi Ponoʻī

(“Hawaii’s Own True Sons”) |

| |

| Official language(s) | English, Hawaiian |

| Demonym | Hawaiian (see notes)[1] |

| Capital | Honolulu |

| Largest city | Honolulu |

| Area | Ranked 43rd in the U.S. |

| - Total | 10,931 sq mi

(28,311 km2) |

| - Width | n/a miles (n/a km) |

| - Length | 1,522 miles (2,450 km) |

| - % water | 41.2 |

| - Latitude | 18° 55′ N to 28° 27′ N |

| - Longitude | 154° 48′ W to 178° 22′ W |

| Population | Ranked 40th in the U.S. |

| - Total | 1,360,301 (2010 Census)[2]

1,211,537 (2000) |

| - Density | 188.6/sq mi (72.83/km2)

Ranked 13th in the U.S. |

| - Median income | $63,746 (5th) |

| Elevation |

|

| - Highest point | Mauna Kea[3]

13,796 ft (4,205 m) |

| - Mean | 3,035 ft (925 m) |

| - Lowest point | Pacific Ocean[3]

0 ft (0 m) |

| Before statehood | Territory of Hawaii |

| Admission to Union | August 21, 1959 (50th) |

| Governor | Neil Abercrombie |

| Lieutenant Governor | Brian Schatz |

| Legislature | State Legislature |

| - Upper house | Senate |

| - Lower house | House of Representatives |

| U.S. Senators | Daniel Inouye (D)

Daniel Akaka (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 1: Colleen Hanabusa (D)

2: Mazie Hirono (D) (list) |

| Time zone | Hawaii-Aleutian time zone: UTC-10

(no daylight saving time) |

| Abbreviations | HI US-HI |

| Website | hawaii.gov |

Hawaii ( i /həˈwaɪ.iː/ or /həˈwaɪʔiː/ in English; Hawaiian: Mokuʻāina o Hawaiʻi) is the newest of the 50 U.S. states (August 21, 1959), and is the only U.S. state made up entirely of islands. It is the northernmost island group in Polynesia, occupying most of an archipelago in the central Pacific Ocean, southwest of the continental United States, southeast of Japan, and northeast of Australia. Hawaii’s natural beauty, warm tropical climate, inviting waters and waves, and active volcanoes make it a popular destination for tourists, surfers, biologists, and volcanologists alike. Due to its mid-Pacific location, Hawaii has many North American and Asian influences along with its own vibrant native culture. Hawaii has over a million permanent residents along with many visitors and U.S. military personnel. Its capital is Honolulu on the island of Oʻahu.

i /həˈwaɪ.iː/ or /həˈwaɪʔiː/ in English; Hawaiian: Mokuʻāina o Hawaiʻi) is the newest of the 50 U.S. states (August 21, 1959), and is the only U.S. state made up entirely of islands. It is the northernmost island group in Polynesia, occupying most of an archipelago in the central Pacific Ocean, southwest of the continental United States, southeast of Japan, and northeast of Australia. Hawaii’s natural beauty, warm tropical climate, inviting waters and waves, and active volcanoes make it a popular destination for tourists, surfers, biologists, and volcanologists alike. Due to its mid-Pacific location, Hawaii has many North American and Asian influences along with its own vibrant native culture. Hawaii has over a million permanent residents along with many visitors and U.S. military personnel. Its capital is Honolulu on the island of Oʻahu.

The state encompasses nearly the entire volcanic Hawaiian Island chain, which comprises hundreds of islands spread over 1,500 miles (2,400 km). At the southeastern end of the archipelago, the eight "main islands" are (from the northwest to southeast) Niʻihau, Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, Molokaʻi, Lānaʻi, Kahoʻolawe, Maui, and Hawaiʻi. The last is by far the largest and is often called "The Big Island" to avoid confusion with the state as a whole. The archipelago is physiographically and ethnologically part of the Polynesian subregion of Oceania.

After Alaska, Florida, and California, Hawaii has the fourth-longest coastline in the United States, which is approximately 750 miles long.

In standard American English, Hawaii is generally pronounced /həˈwaɪ.iː/. In the Hawaiian language, it is generally pronounced [hɐˈwɐiʔi] or [hɐˈvɐiʔi].

Hawaii is one of two states that do not observe daylight saving time, the other being Arizona.

Etymology

The Hawaiian language word Hawaiʻi derives from Proto-Polynesian *Sawaiki, with the reconstructed meaning "homeland";[4] Hawaiʻi cognates are found in other Polynesian languages, including Māori (Hawaiki), Rarotongan (ʻAvaiki), and Samoan (Savaiʻi). (See also Hawaiki).

According to Pukui and Elbert,[5] "Elsewhere in Polynesia, Hawaiʻi—or a cognate—is the name of the underworld or of the ancestral home, but in Hawaii, the name has no meaning."[6]

Geography and environment

The main Hawaiian Islands are:

| Island | Nickname | Location | Area | Area

rank | Highest point | Elevation | Population

(as of 2000) | Density |

| Hawaiʻi[7] | The Big Island |  19°34′N 155°30′W / 19.567°N 155.5°W / 19.567; -155.5 19°34′N 155°30′W / 19.567°N 155.5°W / 19.567; -155.5 | 1 4,028.0 sq mi (10,432.5 km2) | 1st | Mauna Kea | 1 13,796 ft (4,205 m) | 148,677 | 4 37/sq mi (14/km²) |

| Maui[8] | The Valley Isle |  20°48′N 156°20′W / 20.8°N 156.333°W / 20.8; -156.333 20°48′N 156°20′W / 20.8°N 156.333°W / 20.8; -156.333 | 2 727.2 sq mi (1,883.4 km2) | 2nd | Haleakalā | 2 10,023 ft (3,055 m) | 117,644 | 2 162/sq mi (62/km²) |

| Kahoʻolawe[9] | The Target Isle |  20°33′N 156°36′W / 20.55°N 156.6°W / 20.55; -156.6 20°33′N 156°36′W / 20.55°N 156.6°W / 20.55; -156.6 | 8 44.6 sq mi (115.5 km2) | 8th | Puʻu Moaulanui | 7 1,483 ft (452 m) | 0 | 8 0 |

| Lānaʻi[10] | The Pineapple Isle |  20°50′N 156°56′W / 20.833°N 156.933°W / 20.833; -156.933 20°50′N 156°56′W / 20.833°N 156.933°W / 20.833; -156.933 | 6 140.5 sq mi (363.9 km2) | 6th | Lānaʻihale | 6 3,366 ft (1,026 m) | 3,193 | 6 23/sq. mi. (9/km²) |

| Molokaʻi[11] | The Friendly Isle |  21°08′N 157°02′W / 21.133°N 157.033°W / 21.133; -157.033 21°08′N 157°02′W / 21.133°N 157.033°W / 21.133; -157.033 | 5 260.0 sq mi (673.4 km2) | 5th | Kamakou | 4 4,961 ft (1,512 m) | 7,404 | 5 28/sq mi (11/km²) |

| Oʻahu[12] | The Gathering Place |  21°28′N 157°59′W / 21.467°N 157.983°W / 21.467; -157.983 21°28′N 157°59′W / 21.467°N 157.983°W / 21.467; -157.983 | 3 596.7 sq mi (1,545.4 km2) | 3rd | Mount Kaʻala | 5 4,003 ft (1,220 m) | 876,151 | 1 1,468/sq mi (567/km²) |

| Kauaʻi[13] | The Garden Isle |  22°05′N 159°30′W / 22.083°N 159.5°W / 22.083; -159.5 22°05′N 159°30′W / 22.083°N 159.5°W / 22.083; -159.5 | 4 552.3 sq mi (1,430.5 km2) | 4th | Kawaikini | 3 5,243 ft (1,598 m) | 58,303 | 3 106/sq mi (41/km²) |

| Niʻihau[14] | The Forbidden Isle |  21°54′N 160°10′W / 21.9°N 160.167°W / 21.9; -160.167 21°54′N 160°10′W / 21.9°N 160.167°W / 21.9; -160.167 | 7 69.5 sq mi (180.0 km2) | 7th | Mount Pānīʻau | 8 1,250 ft (381 m) | 160 | 7 2/sq mi (1/km²) |

Topography

Pāhoehoe and

ʻA

ʻā lava flows side by side at the Big Island of Hawai

ʻi in September, 2007

A true-color satellite view of Hawaii shows that most of the vegetation on the islands grow on the north-east sides which face the wind. The silver glow around the calmer south-west of the islands is the result of the shelter provided from the islands.

[15] An archipelago situated some 2,000 mi (3,200 km) southwest of the North American mainland,[16] Hawaii is the southernmost state of the United States and the second westernmost state after Alaska. Only Hawaii and Alaska do not share a border with another U.S. state.

Hawaii is the only state of the United States that:

- is not geographically located in North America

- grows coffee

- is completely surrounded by water

- is entirely an archipelago

- has a royal palace

- does not have a straight line in its state boundary

Hawaii’s tallest mountain, Mauna Kea, stands at 13,796 ft (4,205 m)[17] but is taller than Mount Everest if followed to the base of the mountain, which, lying at the floor of the Pacific Ocean, rises about 33,500 ft (10,200 m).[18]

The eight main islands, Hawaiʻi, Maui, Oʻahu, Kahoʻolawe, Lanaʻi, Molokaʻi, Kauaʻi and Niʻihau are accompanied by many others. Kaʻala is a small island near Niʻihau that is often overlooked. The Northwest Hawaiian Islands are a series of nine small, older masses northwest of Kauaʻi that extend from Nihoa to Kure that are remnants of once much larger volcanic mountains. There are also more than 100 small rocks and islets, such as Molokini, that are either volcanic, marine sedimentary or erosional in origin, totaling 130 or so across the archipelago.[19]

Geology

All the Hawaiian islands were formed from volcanic activity initiated at an undersea magma source called a hotspot. As the tectonic plate beneath much of the Pacific Ocean moves to the northwest, the hot spot remains stationary, slowly creating new volcanoes. Due to the hotspot’s location, the only active volcanoes are located around the southern half of the Big Island. The newest volcano, Lōʻihi Seamount, is located south of the Big Island’s coast.

The last volcanic eruption outside the Big Island occurred at Haleakalā on Maui before the late 18th century, though it could have been hundreds of years earlier.[20] In 1790, Kīlauea exploded with the deadliest eruption (of the modern era) known to have occurred in what is now the United States.[21] As many as 5,405 warriors and their families marching on Kīlauea were killed by that eruption.[22]

Volcanic activity and subsequent erosion have created impressive geological features. The Big Island has the third highest point among the world’s islands.[23]

Slope instability of the volcanoes has generated damaging earthquakes with related tsunamis, particularly in 1868 and 1975.[24]

Flora and fauna

Because the islands are so far from other land habitats, life before human activity is said to have arrived by the “3 W’s”: wind (carried through the air), waves (brought by ocean currents), and wings (birds, insects, and whatever they brought with them). This isolation, and the wide range of environments (extreme altitude, tropical climate) produced a vast array of endemic flora and fauna (see Endemism in the Hawaiian Islands). Hawaii has more endangered species and has lost a higher percentage of its endemic species than any other U.S. state.[25]

Protected areas

Several areas in Hawaii are under the protection of the National Park Service.[26] Hawaii has two national parks: Haleakala National Park near Kula, on Maui, includes Haleakalā, the dormant volcano that formed east Maui; and Hawaii Volcanoes National Park in the southeast region of the island of Hawaiʻi, which includes the active volcano Kīlauea and its various rift zones.

There are three national historical parks: Kalaupapa National Historical Park in Kalaupapa, Molokaʻi, the site of a former Hansen’s disease colony; Kaloko-Honokōhau National Historical Park in Kailua-Kona on the island of Hawaiʻi; and Puʻuhonua o Hōnaunau National Historical Park, an ancient place of refuge. Other areas under the control of the National Park Service include Ala Kahakai National Historic Trail on the Big Island and the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor on Oʻahu.

The Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument was proclaimed by President George W. Bush on June 15, 2006. The monument covers roughly 140,000 square miles (360,000 km2) of reefs, atolls and shallow and deep sea out to 50 miles (80 km) offshore in the Pacific Ocean, larger than all of America’s National Parks combined.[27]

Climate

Sunset in

Kona. The colors of the sunset are partly due to

vog.

Hawaii’s climate is typical for the tropics, although temperatures and humidity tend to be a bit less extreme due to near-constant trade winds from the east. Summer highs are usually in the upper 80s °F, (around 31°C) during the day and mid 70s, (around 24 °C) at night. Winter day temperatures are usually in the low to mid 80s, (around 28 °C) and (at low elevation) seldom dipping below the mid 60s (18 °C) at night. Snow, not usually associated with the tropics, falls at 4,205 metres (13,796 ft) on Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa on the Big Island in some winter months. Snow rarely falls on Haleakala. Mount Waiʻaleʻale, on Kauaʻi, has the second highest average annual rainfall on Earth, about 460 inches (11.7 m). Most of Hawaii has only two seasons: the dry season from May to October, and the wet season from October to April.[28]

Local climates vary considerably on each island, grossly divisible into windward (Koʻolau) and leeward (Kona) areas based upon location relative to the higher mountains. Windward sides face cloud cover, so resorts concentrate on sunny leeward coasts.

Monthly normal low and high temperatures for various Hawaiian cities[29] | City | Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | May | Jun. | Jul. | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. |

| Hilo | 64°F / 17.8°C | 64°F / 17.8°C | 65°F / 18.3°C | 66°F / 18.9°C | 67°F / 19.4°C | 68°F / 20.0°C | 69°F / 20.6°C | 69°F / 20.6°C | 69°F / 20.6°C | 68°F / 20.0°C | 67°F / 19.4°C | 65°F / 18.3°C |

| 79°F / 26.1°C | 79°F / 26.1°C | 79°F / 26.1°C | 79°F / 26.1°C | 81°F / 27.2°C | 82°F / 27.8°C | 82°F / 27.8°C | 83°F / 28.3°C | 83°F / 28.3°C | 83°F / 28.3°C | 81°F / 27.2°C | 80°F / 26.7°C |

| Honolulu | 66°F / 18.9°C | 65°F / 18.3°C | 67°F / 19.4°C | 68°F / 20.0°C | 70°F / 21.1°C | 72°F / 22.2°C | 74°F / 23.3°C | 75°F / 23.9°C | 74°F / 23.3°C | 73°F / 22.8°C | 71°F / 21.7°C | 68°F / 20.0°C |

| 80°F / 26.7°C | 81°F / 27.2°C | 82°F / 27.8°C | 83°F / 28.3°C | 85°F / 29.4°C | 87°F / 30.6°C | 88°F / 31.1°C | 89°F / 31.7°C | 89°F / 31.7°C | 87°F / 30.6°C | 84°F / 28.9°C | 82°F / 27.8°C |

| Kahului | 63°F / 17.2°C | 63°F / 17.2°C | 65°F / 18.3°C | 66°F / 18.9°C | 67°F / 19.4°C | 69°F / 20.6°C | 71°F / 21.7°C | 71°F / 21.7°C | 70°F / 21.1°C | 69°F / 20.6°C | 68°F / 20.0°C | 65°F / 18.3°C |

| 80°F / 26.7°C | 81°F / 27.2°C | 82°F / 27.8°C | 82°F / 27.8°C | 84°F / 28.9°C | 86°F / 30.0°C | 87°F / 30.6°C | 88°F / 31.1°C | 88°F / 31.1°C | 87°F / 30.6°C | 84°F / 28.9°C | 82°F / 27.8°C |

| Lihuʻe | 65°F / 18.3°C | 66°F / 18.9°C | 67°F / 19.4°C | 69°F / 20.6°C | 70°F / 21.1°C | 73°F / 22.8°C | 74°F / 23.3°C | 74°F / 23.3°C | 74°F / 23.3°C | 73°F / 22.8°C | 71°F / 21.7°C | 68°F / 20.0°C |

| 78°F / 25.6°C | 78°F / 26.6°C | 78°F / 26.6°C | 79°F / 26.1°C | 81°F / 27.2°C | 83°F / 28.3°C | 84°F / 28.9°C | 85°F / 29.4°C | 85°F / 29.4°C | 84°F / 28.9°C | 81°F / 27.2°C | 79°F / 26.1°C |

History

Hawaii is one of four states that were independent prior to becoming part of the United States, along with the Vermont Republic (1791), the Republic of Texas (1845), and the California Republic (1846), and one of two, along with Texas, that had formal diplomatic recognition internationally.[30] The Kingdom of Hawaii was sovereign from 1810 until 1893 when the monarchy was overthrown by resident American (and some European) businessmen. It was an independent republic from 1894 until 1898, when it was annexed by the United States as a territory, becoming a state in 1959.[31]

Hawaii was the target of a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor by Imperial Japan on December 7, 1941. The attack on Pearl Harbor and other military and naval installations on Oʻahu, carried out by aircraft and by midget submarines brought the United States into World War II.

Pre-European contact—Ancient Hawaiʻi (800–1778)

Main article:

Ancient HawaiiThe earliest habitation supported by archaeological evidence dates to as early as 300 BCE, probably by Polynesian settlers from the Marquesas, followed by a second wave of migration from Raiatea and Bora Bora in the 11th century. The first recorded European contact with the islands was in 1778 by British explorer James Cook.

Polynesians from the Marquesas and possibly the Society Islands may have first populated the Hawaiian Islands between 300 and 500 CE. There is a great deal of debate regarding these dates.[32]

Some archaeologists and historians believe that an early settlement from the Marquesas and a later wave of immigrants from Tahiti, c. 1000 introduced a new line of high chiefs, the Kapu system, the practice of human sacrifice and the building of heiaus. This later immigration is detailed in folk tales about Paʻao. Other authors argue that there is no archaeological or linguistic evidence for a later influx of Tahitian settlers, and that Paʻao must be regarded as a myth.

Regardless of the question of Paʻao, historians agree that the history of the islands was marked by a slow but steady growth in population and the size of the chiefdoms, which grew to encompass whole islands. Local chiefs, called aliʻi, ruled their settlements and launched wars to extend their sway and defend their communities from predatory rivals.

James Cook—European arrival and the Kingdom of Hawaii (1778–1893)

The 1778 arrival of British explorer James Cook was Hawaii’s first documented contact with European explorers. Cook named the islands the "Sandwich Islands" in honor of his sponsor John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich. He published the islands' location and reported the native name as Owyhee. This spelling lives on in Owyhee County, Idaho, after three Hawaiian members of a trapping party killed in that area.

Cook visited the islands twice. During his second visit in 1779, he attempted to abduct the King of the Big Island of Hawaii, Kalaniʻōpuʻu, and hold him as ransom for the return of a ship's boat that was taken by a minor chief and his men, a tactic that had worked for Cook in Tahiti and other islands.[33] Kalaniʻōpuʻu and his supporters fought back and Cook and four Marines were killed as Cook's party retreated to the beach and launched their boats.

After Cook's visit and the publication of several books relating his voyages, the Hawaiian islands received many European visitors: explorers, traders, and eventually whalers who found the islands a convenient harbor and source of supplies. Early British influence can be seen in the design of the flag of Hawaii which has the British Union Flag in the corner.

These visitors introduced diseases to the once-isolated islands and the Hawaiian population plunged precipitously[34] because native Hawaiians had no resistance to influenza, smallpox, and measles, among others. During the 1850s, measles killed a fifth of Hawaii's people.[35]

Historical records indicated that the earliest immigration of the Chinese came from Guangdong province: a few sailors in 1778 with Captain Cook's journey, more in 1788 with Kaina, and some in 1789 with an American trader who settled in Hawaii in the late 18th century.

House of Kamehameha

During the 1780s and 1790s, chiefs were often fighting for power. After a series of battles that ended in 1795 and forced cession of the island of Kauaʻi in 1810, all inhabited islands were subjugated under a single ruler who became known as King Kamehameha the Great. He established the House of Kamehameha, a dynasty that ruled the kingdom until 1872.

After Kamehameha II inherited the throne in 1819, missionaries to Hawaii converted many Hawaiians to Christianity. Their influence ended many ancient practices, and Kamehameha III was the first Christian king. Missionary leaders included Protestant Hiram Bingham I and Joseph F. Smith of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Father Damien, a Roman Catholic priest, was canonized for his work in the isolated leper colony of Kalaupapa on the island of Molokaʻi. Other missionaries and their descendants, such as Henry Perrine Baldwin, became active in commercial and political affairs, leading to future conflicts.

The death of the bachelor King Kamehameha V—who did not name an heir—resulted in the popular election of Lunalilo over Kalākaua. Lunalilo died the next year, also without naming an heir. Perhaps "the People's King" (Lunalilo) wanted the people to choose his successor as they had chosen him. In 1874 the election was contested within the legislature between Kalākaua and Emma. This led to riots and the landing of U.S. and British troops, and governance passed to the House of Kalākaua.

1887 Constitution

In 1887, Kalākaua was forced to sign the 1887 Constitution of the Kingdom of Hawaii, which stripped the king of much of his authority. There was a property qualification for voting, which disenfranchised many poorer Hawaiians and favored the wealthier white community. Resident whites were allowed to vote, but resident Asians were excluded. Because the 1887 Constitution was signed under threat of violence, it is known as the "Bayonet Constitution". King Kalākaua, reduced to a figurehead, reigned until his death in 1891. His sister, Liliʻuokalani, succeeded him on the throne.

Ship's landing force at the time of the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy, January 1893.

In 1893, Queen Liliʻuokalani announced plans for a new constitution. On January 14, 1893, a group of mostly Euro-American business leaders and residents formed a Committee of Safety to overthrow the Kingdom and seek annexation by the United States. United States Government Minister John L. Stevens, responding to a request from the Committee of Safety, summoned a company of U.S. Marines. As one historian noted, the presence of these troops effectively made it impossible for the monarchy to protect itself.[36]

Overthrow of 1893—the Republic of Hawaii (1894–1898)

In January 1893, Queen Liliʻuokalani was overthrown and replaced by a Provisional Government composed of members of the Committee of Safety. Controversy filled the following years as the queen tried to re-establish her throne. The administration of President Grover Cleveland commissioned the Blount Report, which concluded that the removal of Liliʻuokalani was illegal. The U.S. government first demanded that Queen Liliʻuokalani be reinstated, but the Provisional Government refused. Congress followed with another investigation, and submitted the Morgan Report on February 26, 1894, which found all parties (including Minister Stevens) with the exception of the queen "not guilty" from any responsibility for the overthrow.[37] The accuracy and impartiality of both the Blount and Morgan reports has been questioned by partisans on both sides of the debate over the events of 1893.[36][38][39][40]

In 1993, a joint Apology Resolution regarding the overthrow was passed by Congress and signed by President Clinton, apologizing for the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom.[40] It is the first time in American history that the United States government has apologized for overthrowing the government of a sovereign nation.

ʻIolani Palace in

Honolulu, formerly the residence of the Hawaiian monarch, was the capitol of the Republic of Hawaii.

The Provisional Government of Hawaii ended on July 4, 1894, replaced by the Republic of Hawaii.

The first Japanese immigrants arrived in Hawaii in 1885 as contract laborers for the sugar cane and pineapple plantations. Puerto Rican immigration to Hawaii began when Puerto Rico's sugar industry was devastated by two hurricanes in 1899. The devastation caused a world wide shortage in sugar and a huge demand for the product from Hawaii. Hawaiian sugar plantation owners began to recruit the jobless, but experienced, laborers in Puerto Rico. Two distinct waves of Korean immigration to Hawaii have occurred in the last century. The first arrived in between 1903 and 1924; the second wave began in 1965.

Annexation—the Territory of Hawaii (1898–1959)

After William McKinley won the presidential election in 1896, Hawaii's annexation to the U.S. was again discussed. The previous president, Grover Cleveland, was a friend of Queen Liliʻuokalani. McKinley was open to persuasion by U.S. expansionists and by annexationists from Hawaii. He met with three annexationists from Hawaii: Lorrin Thurston, Francis March Hatch and William Ansel Kinney. After negotiations, in June 1897, Secretary of State John Sherman agreed to a treaty of annexation with these representatives of the Republic of Hawaii.[41]

The treaty was never ratified by the U.S. Senate. Instead, the Newlands Resolution by both houses of Congress annexed the Republic to the United States and it became the Territory of Hawaii. Despite some opposition in the islands, the Newlands Resolution was passed by the House June 15, 1898, by a vote of 209 to 91, and by the Senate on July 6, 1898, by a vote of 42 to 21.

In 1900, Hawaii was granted self-governance and retained ʻIolani Palace as the territorial capitol building. Despite several attempts to become a state, Hawaii remained a territory for sixty years. Plantation owners and key capitalists, who maintained control through financial institutions, or "factors," known as the "Big Five", found territorial status convenient, enabling them to continue importing cheap foreign labor; such immigration was prohibited in various states.

Political Changes of 1954—the State of Hawaii (1959–present)

All representative districts voted at least 93% in favor of Admission acts. Ballot (inset) and referendum results for the Admission Act of 1959

In the 1950s the power of the plantation owners was finally broken by descendants of immigrant laborers. Because they were born in a U.S. territory, they were legal U.S. citizens. The Hawaii Republican Party, strongly supported by plantation owners, was voted out of office. The Democratic Party of Hawaii dominated politics for 40 years. Expecting to gain full voting rights, Hawaii's residents actively campaigned for statehood.

In March 1959, Congress passed the Hawaii Admission Act and U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed it into law. (The act excluded Palmyra Atoll, part of the Kingdom and Territory of Hawaii, from the new state.) On June 27 of that year, a referendum asked residents of Hawaii to vote on the statehood bill. Hawaii voted 17 to 1 to accept. The choices were to accept the Act or to remain a territory, without the option of independence.[42][43][44] The United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization later removed Hawaii from the United Nations list of Non-Self-Governing Territories.

After statehood, Hawaii quickly modernized via construction and rapidly growing tourism economy. Later, state programs promoted Hawaiian culture. The Hawaii State Constitutional Convention of 1978 incorporated programs such as the Office of Hawaiian Affairs to promote indigenous language and culture.

Cities and towns

Honolulu is the largest city and capital of Hawaii.

The movement of the Hawaiian royal family from the Big Island to Maui, and subsequently to Oʻahu, explains why population centers exist where they do today. Kamehameha III chose the largest city, Honolulu, as his capital because of its natural harbor, the present-day Honolulu Harbor.

Now the state capital, Honolulu is located along the southeast coast of Oʻahu. The previous capital was Lahaina, Maui and before that Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. Some major towns are Hilo, Kāneʻohe, Kailua, Pearl City, Waipahu, Kahului, Kailua-Kona, Kīhei, and Līhuʻe.

Demographics

Population

| Historical populations |

| Census | Pop. |

| %± |

| 1900 | 154,001 |

| — |

| 1910 | 191,874 |

| 24.6% |

| 1920 | 255,881 |

| 33.4% |

| 1930 | 368,300 |

| 43.9% |

| 1940 | 422,770 |

| 14.8% |

| 1950 | 499,794 |

| 18.2% |

| 1960 | 632,772 |

| 26.6% |

| 1970 | 769,913 |

| 21.7% |

| 1980 | 964,691 |

| 25.3% |

| 1990 | 1,108,229 |

| 14.9% |

| 2000 | 1,211,537 |

| 9.3% |

| 2010 | 1,360,301 |

| 12.3% |

| Source: 1910-2010[45] |

As of 2005, Hawaii has an estimated population of 1,275,194, an increase of 13,070, or 1.0%, from the prior year and an increase of 63,657, or 5.3%, since 2000. This includes a natural increase of 48,111 people (that is 96,028 births minus 47,917 deaths) and an increase due to net migration of 16,956 people into the state. Immigration from outside the United States resulted in a net increase of 30,068 people, and migration within the country produced a net loss of 13,112 people. The center of population of Hawaii is located between the two islands of Oʻahu and Molokaʻi.[46]

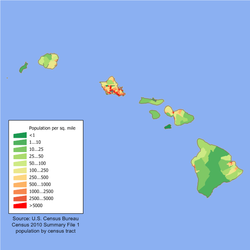

Hawaii has a de facto population of over 1.3 million due to large military and tourist populations. Oʻahu, nicknamed "The Gathering Place", is the most populous island (and has the highest population density), with a resident population of just under one million in 597 square miles (1,546 km2), about 1,650 people per square mile (for comparison, New Jersey, which has 8,717,925 people in 7,417 square miles (19,210 km2) is the most-densely populated state with 1,134 people per square mile.)[47] Hawaii's 1,275,194 people, spread over 6,423 square miles (16,640 km2) (including many unpopulated islands) results in an average population density of 188.6 persons per square mile,[48] which makes Hawaii less densely populated than Ohio and Illinois.[49]

The average projected lifespan of those born in Hawaii in 2000 was 79.8 years (77.1 years if male, 82.5 if female), longer than any other state.[50]

U.S. military personnel make up approximately 1.3% of the population in the islands.

Race and ethnicity

According to the 2008 American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, White Americans made up 27.1% of Hawaii's population; 24.8% were non-Hispanic whites. Blacks or African Americans made up 2.4% (2.3% non-Hispanic). American Indians made up 0.2% ( 0.1% non-Hispanic). Asian Americans made up 38.5% (37.6% non-Hispanic). Pacific Islander Americans made up 9.0% (8.6% non-Hispanic). Individuals from some other race made up 1.4% (0.1% non-Hispanic). Multiracial Americans made up 21.4% (17.8% non-Hispanic). Hispanics and Latinos (of any race) made up 8.7%.[51]

Hawaii has the highest percentage of Asian Americans, mainly 175,000 Filipino Americans and 161,000 Japanese Americans. In addition, there are roughly 53,000 Chinese Americans and 40,000 Korean Americans. Indigenous Hawaiians number 70,000 (or 5.5%). Over 110,000 Hispanic and Latino Americans make Hawaii their home. Mexicans number 37,000; Puerto Ricans number 35,000. Also, Hawaii has the highest percentage of Multiracial Americans; mixed-race individuals form roughly 21% of Hawaii's population. Eurasian Americans are a prominent mixed-race group; there are roughly 61,000 Eurasian Americans in Hawaii.[51]

The five largest European ancestries in Hawaii are German (7.4%), Irish (5.2%), English (4.6%), Portuguese (4.3%), and Italian (2.7%).

Approximately 82.2% of Hawaii's residents were born in the United States. Roughly 75.0% of the foreign-born residents hail from Asia.[52]

Hawaii is a majority-minority state. Non-Hispanic whites do not form a majority. Hawaii was the second majority-minority state. Both Hawaii and New Mexico have been majority-minority since the early 20th century.

Ancestry groups

The largest ancestry groups in Hawaii as of 2008 are in the table at right. The third group of foreigners to arrive upon Hawaii's shores, after those from Polynesia and Europe, was from Han China. Chinese workers on Western trading ships settled in Hawaii starting in 1789. In 1820 the first American missionaries came to preach Christianity and teach the Hawaiians Western ways. They were instrumental in convincing the Hawaiian Chiefs to end human sacrifice.[citation needed]

A large proportion of Hawaii's population is now of Asian ancestry (especially Chinese, Japanese and Filipino.) Many are descendants of those immigrants brought to work on the sugar plantations in the 1850s and after. The first 153 Japanese immigrants arrived in Hawaii on June 19, 1868. They were not "legally" approved by the Japanese government because the contract was between a broker and the Tokugawa shogunate, by then replaced by the Meiji Restoration. The first Japanese government-approved immigrants arrived on February 9, 1885 after Kalākaua's petition to Emperor Meiji when Kalākaua visited Japan in 1881.[citation needed]

Almost 13,000 Portuguese had come by 1899. They too worked on the sugar plantations. By October 17, 1901, 5,000 Puerto Ricans had made new homes on the four islands.[citation needed]

Languages

The State of Hawaii has two official languages recognized in its 1978 constitution: English and Hawaiian. Article XV, Section 4, specifies that "Hawaiian shall be required for public acts and transactions only as provided by law" [italic added]. Hawaii Creole English (locally referred to as 'Pidgin') is the native language of many born-and-raised residents and is a second language for many other residents.

English

As of the 2000 Census, 73.44% of Hawaii residents age 5 and older speak only English at home.[53]

According to the 2008 American Community Survey, 74.6% of Hawaii's residents over the age of five speak only English at home.[51]

Minority languages

In addition, 2.6% of the state's residents speak Spanish; 1.6% speak other Indo-European languages; 21.0% speak an Asian language; and 0.2% speak a different language at home.[51]

After English, other popular languages are Tagalog (most are bilingual in Filipino), Japanese, and Ilokano. Significant European immigrants and descendants also speak their native languages; the most numerous are Spanish, German, Portuguese and French.

Tagalog speakers make up 5.37% (which includes non-native speakers of Filipino language, the national co-official Tagalog-based language), followed by Japanese at 4.96%, Ilokano at 4.05%, Chinese at 1.92%, Hawaiian at 1.68%, Spanish at 1.66%, Korean at 1.61%, and Samoan at 1.01%.[53]

Hawaiian

The Hawaiian language has about 2000 native speakers, less than 0.1% of the total population.[54] According to the United States Census, there were 27,160 total speakers of the language in Hawaii in 2005.[55]

Hawaiian is a member of the Polynesian branch of the Austronesian family. It began to develop around 1000 AD, when Marquesans or Tahitians colonized Hawaii. Those Polynesians remained in the islands, thereby becoming the Hawaiian people. Their language developed into the Hawaiian language. Before the arrival of Captain James Cook, the Hawaiian language had no written form. That form was developed mainly by American Protestant missionaries during 1820–1826. They assigned letters from the Latin alphabet that corresponded to the Hawaiian sounds.

Interest in Hawaiian increased significantly in the late 20th century. With the help of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, specially designated immersion schools were established where all subjects would be taught in Hawaiian. Also, the University of Hawaii developed a Hawaiian language graduate studies program. Municipal codes were altered to favor Hawaiian place and street names for new civic developments.

Hawaiian distinguishes between long and short vowels. In modern practice, vowel length is indicated with a macron (kahakō). Also, Hawaiian uses the glottal stop as a consonant (ʻokina). It is written as a symbol similar to the apostrophe or opening single quote.

Hawaiian-language newspapers published from 1834–1948 and traditional native speakers of Hawaiian generally omit the marks in their own writing. The ʻokina and kahakō are intended to help non-native speakers.

Hawaiian Pidgin

Some locals speak Hawaii Creole English (HCE), often called "pidgin". The lexicon of HCE derives mainly from English but also has words from Hawaiian, Chinese, Japanese, Ilocano and Tagalog and Portuguese. During the 19th century, the increase in immigration (mainly from China, Japan, Portugal—and especially from the Azores archipelago—and Spain), caused a variant of English to develop. By the early 20th century pidgin speakers had children who acquired the pidgin as their first language. HCE speakers use some Hawaiian words without those words being considered archaic. Most place names are retained from Hawaiian, as are some names for plants or animals. For example, tuna fish are often called ahi.

International Market Place, Honolulu, 1958.

HCE speakers have modified the meanings of certain English words. For example, "aunty" and "uncle" refer to any adult who is a friend, or to show respect for an elder. Simplified grammar is used. For example, instead of "It is hot today, isn't it?", an HCE speaker would say simply "stay hot, eh?" When a word does not come to mind quickly, the term "da kine" refers to any word you cannot think of. Through the surfing boom in Hawaii, HCE has influenced surfer slang. Some HCE expressions, such as brah and da kine, have found their way to other places.

Spelling of state name

A somewhat divisive political issue arose when the constitution of the State of Hawaii added Hawaiian as a second official state language: the exact spelling of the state's name. In the Hawaii Admission Act that granted Hawaiian statehood, the federal government recognized Hawaii to be the official state name. Official government publications, as well as department and office titles, use the traditional Hawaiian spelling, with no symbols for glottal stops or vowel length.[56] In contrast, some private entities, including a local newspaper, do use such symbols.

The title of the state constitution is "The Constitution of the State of Hawaii". In Article XV, Section 1 uses "The State of Hawaii", Section 2 "the island of Oahu", Section 3 "The Hawaiian flag", and Section 5 specifies the state motto as "Ua mau ke ea o ka aina i ka pono". Since these documents predate the modern use of the ʻokina and the kahakō in Hawaiian orthography, the diacritics were not used.

The nuances in the Hawaiian language debate are often not obvious or well-appreciated among English speakers outside Hawaii.[57]

Religion

According to data provided by religious establishments, religion in Hawaii in 2000 was distributed as follows:[58][59][60]

The largest denominations by number of adherents were the Catholic Church with 240,813 in 2000[61] and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 68,128 in 2009.[62]

"Other" are religions other than Christianity, Buddhism, or Judaism; this group includes Bahá'í Faith, Confucianism, Daoism, the Hawaiian religion, Hinduism, Islam, Sikhism, Shintoism, Zoroastrianism, and other religions.

"Unaffiliated" refers to people who do not belong to a congregation; this group includes agnostics, atheists, humanists, and the irreligious.

A 2009 Gallup poll found religion was distributed as follows, excluding those of other non-Judeo-Christian religions and those who had "no opinion":[63]

A special case is Hoʻoponopono, an ancient Hawaiian practice of reconciliation and forgiveness, combined with prayer. It is both philosophy and way of life. Traditionally hoʻoponopono is practiced by healing priests or kahuna lapaʻau among family members of a person who is physically ill.

Economy

The history of Hawaii can be traced through a succession of dominant industries: sandalwood,[64] whaling,[65] sugarcane (see Sugar plantations in Hawaii), pineapple, military, tourism, and education. Since statehood in 1959, tourism has been the largest industry, contributing 24.3% of the Gross State Product (GSP) in 1997, despite efforts to diversify. The gross output for the state in 2003 was US$47 billion; per capita income for Hawaii residents was US$30,441.

Hawaiian exports include food and apparel. These industries play a small role in the Hawaiian economy, however, due to the considerable shipping distance to viable markets, such as the West Coast of the United States. Food exports include coffee (see coffee production in Hawaii), macadamia nuts, pineapple, livestock, and sugarcane. Agricultural sales for 2002, according to the Hawaii Agricultural Statistics Service, were US$370.9 million from diversified agriculture, US$100.6 million from pineapple, and US$64.3 million from sugarcane.

Hawaii has a relatively high state tax burden. In 2003, Hawaii residents had the highest state tax per capita at US$2,838. This is partly because education, health care and social services are all provided directly by the state, as opposed to local government in all other states.

Millions of tourists contribute to the tax take by paying the general excise tax and hotel room tax; thus not all taxes come directly from residents. Business leaders, however, consider the state's tax burden too high, contributing to both higher prices and the perception of an unfriendly business climate.[66] See the list of businesses in Hawaii for more on commerce.

Hawaii was one of the few states to control gasoline prices through a Gas Cap Law. Since oil company profits in Hawaii compared to the mainland U.S. were under scrutiny, the law tied local gasoline prices to those of the mainland. It took effect in September 2005 amid price fluctuations caused by Hurricane Katrina, but was suspended in April 2006.

As of January 2010, the state's unemployment rate was 6.9%.[67]

Cost of living

The cost of living in Hawaii, specifically Honolulu, is quite high compared to most major cities in the United States. However, the cost of living in Honolulu is 6.7% lower than in New York, NY and 3.6% lower than in San Francisco, CA.[68] These numbers may not take into account certain costs, such increased travel costs for longer flights, additional shipping fees, and the loss of promotional participation opportunities for customers "outside the continental United States". While some online stores do offer free shipping on orders to Hawaii,[69] many merchants exclude Hawaii, Alaska, Puerto Rico and certain other US territories.

The median home value in Hawaii in the 2000 US Census was $272,700 while the national median home value was less than half, at $119,600. Hawaii home values were the highest of all states, including California with a median home value of $211,500.[70] More recent research from the National Association of Realtors® places the 2010 median sale price of a single family home in Honolulu, Hawaii at $607,600 and the US median sales price at 173,200. The sale price of single family homes in Hawaii was the highest of any US city in 2010, just above the "Silicon Valley" area of California ($602,000).[71]

Culture

The aboriginal culture of Hawaii is Polynesian. Hawaii represents the northernmost extension of the vast Polynesian triangle of the south and central Pacific Ocean. While traditional Hawaiian culture remains only as vestiges in modern Hawaiian society, there are reenactments of the ceremonies and traditions throughout the islands. Some of these cultural influences are strong enough to affect the United States at large, including the popularity (in greatly modified form) of luaus and hula.

Hawaii is home to numerous cultural events. The annual Merrie Monarch Festival is an international Hula competition.[72] The state is also home to the Hawaii International Film Festival, the premier film festival for pacific rim cinema.[73] Honolulu is also home to the state's long running GLBT film festival, the Rainbow Film Festival.[74][75]

Health

Hawaii's health care system insures 92% (2009) of residents. Under the state's plan, businesses are required to provide insurance to employees who work more than twenty hours per week. Heavy regulation of insurance companies helps keep the cost to employers down. Due in part to heavy emphasis on preventive care, Hawaiians require hospital treatment less frequently than the rest of the United States, while total health care expenses (measured as a percentage of state GDP) are substantially lower. Given these achievements, proponents of universal health care elsewhere in the U.S. sometimes use Hawaii as a model for proposed federal and state health care plans. Critics, however, claim that Hawaii's success is due at least in part to its mild climate and to its isolated status and an economy based on tourism: businesses unhappy with paying the plan's premiums find it difficult to relocate elsewhere.[76]

Education

Public schools

Hawaii has the U.S.' only school system that is unified statewide. Policy decisions are made by the fourteen-member state Board of Education. The Board sets policy and hires the superintendent of schools, who oversees the state Department of Education. The Department of Education is divided into seven districts, four on Oʻahu and one for each of the three other counties.

The main rationale for centralization is to combat inequalities between highly populated Oʻahu and the more rural Neighbor Islands, and between lower-income and more affluent areas. In most of the United States, schools are funded from local property taxes.

Educators struggle with children of non-native-English-speaking immigrants, whose cultures are different from those of the mainland (where most course materials and testing standards originate).

Public elementary, middle, and high school test scores in Hawaii are below national averages on tests mandated under the No Child Left Behind Act. Some of the gap has been attributed to the Hawaii Board of Education's requirement that all eligible students take these tests and report all student test scores. Other states, for example, Texas and Michigan do not. Results reported in August, 2005, indicate that of 282 schools across the state, 185 (2/3) failed to reach federal minimum performance standards in math and reading.[77]

On the other hand, the ACT college placement tests show that in 2005, seniors scored slightly above the national average (21.9 compared with 20.9).[78] In the widely accepted SAT examinations, Hawaii's college-bound seniors tend to score below the national average in all categories except mathematics.

Other schools

Hawaii educates more students in independent institutions of secondary education than any other state in the United States. It has four of the largest independent schools: ʻIolani School, Kamehameha Schools, Mid-Pacific Institute, and Punahou School. The second Buddhist high school in the United States, and first Buddhist high school in Hawaii, Pacific Buddhist Academy, was founded in 2003. The first native controlled public charter school was the Kanu O Ka Aina New Century Charter School.

Independent and charter schools can select their students, while the regular public schools must take all students in their district. The Kamehameha Schools are the only schools in the United States that openly grant admission to students based on ancestry, and the wealthiest schools in the United States, if not the world, having over nine billion US dollars in estate assets. In 2005, Kamehameha enrolled 5,398 students, 8.4% of the Native Hawaiian children in the state.[79]

Colleges and universities

Graduates of secondary schools in Hawaii often enter directly into the work force. Some attend colleges and universities on the mainland or other countries, and the rest attend an institution of higher learning in Hawaii.

The largest is the University of Hawaii System. It consists of: the research university at Mānoa; two comprehensive campuses Hilo and West Oʻahu; and seven Community Colleges. Private universities include Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Chaminade University of Honolulu, Hawaii Pacific University, Wayland Baptist University, or University of the Nations. The Saint Stephen Diocesan Center is a seminary of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Honolulu.

Law and government

The state government of Hawaii is modeled after the federal government with adaptations originating from the kingdom era of Hawaiian history. As codified in the Constitution of Hawaii, there are three branches of government: executive, legislative and judicial.

The executive branch is led by the Governor of Hawaii assisted by the Lieutenant Governor of Hawaii, both elected on the same ticket. The governor, in residence at the grounds of Washington Place, is the only public official elected for the state government in a statewide race; all others are appointed by the governor. The lieutenant governor acts as the Secretary of State. The governor and lieutenant governor oversee twenty agencies and departments from offices in the State Capitol.

The legislative branch consists of the Hawaii State Legislature—twenty-five members of the Hawaii Senate led by the President of the Senate and fifty-one members of the Hawaii House of Representatives led by the Speaker of the House. They also govern from the State Capitol. The judicial branch is led by the highest state court, the Hawaii State Supreme Court, which uses Aliʻiōlani Hale as its chambers. Lower courts are organized as the Hawaii State Judiciary.

Unique to Hawaii is the lack of municipal governments. All local governments are administered at the county level. The only incorporated area in the state is a consolidated city–county: Honolulu County, which governs the entire island of Oahu. County executives are the Mayor of Hawaii, Mayor of Honolulu, Mayor of Kauaʻi and Mayor of Maui, all elected in nonpartisan races.

Federal government

Hawaii is represented in the United States Congress by four people:

Senators Inouye and Akaka were both born in 1924, making them the oldest current Senate duo.

All federal officers in Hawaii administer their duties from the Prince Kūhiō Federal Building near the Aloha Tower and Honolulu Harbor, including the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Internal Revenue Service and the United States Secret Service. The building is the site of the federal courts and the offices of the United States Attorney for the District of Hawaii, principal police officer of the Department of Justice in the United States District Court for the District of Hawaii.

National politics

Presidential elections results | Year | Republican | Democratic |

| 2008 | 26.58% 120,446 | 71.85% 325,588 |

| 2004 | 45.26% 194,191 | 54.01% 231,708 |

| 2000 | 37.46% 137,845 | 55.79% 205,286 |

| 1996 | 31.64% 113,943 | 56.93% 205,012 |

| 1992 | 36.70% 136,822 | 48.09% 179,310 |

| 1988 | 44.75% 158,625 | 54.27% 192,364 |

| 1984 | 55.10% 185,050 | 43.82% 147,154 |

| 1980 | 42.90% 130,112 | 44.80% 135,879 |

| 1976 | 48.06% 140,003 | 50.59% 147,375 |

| 1972 | 62.48% 168,865 | 37.52% 101,409 |

| 1968 | 38.70% 91,425 | 59.83% 141,324 |

| 1964 | 21.24% 44,022 | 78.76% 163,249 |

| 1960 | 49.97% 92,295 | 50.03% 92,410 |

Hawaii supported Democrats in 10 of the last 12 presidential elections. The exceptions were 1972 and 1984. In 2004, John Kerry won the state's 4 electoral votes by a margin of 9 percentage points with 54% of the vote. Every county supported the Democratic candidate. In 1964, favorite son candidate Senator Hiram Fong of Hawaii sought the Republican presidential nomination, while Patsy Mink ran in the Oregon primary in 1972.

Honolulu native Barack Obama, serving as United States Senator from Illinois, was elected President of the United States on November 4, 2008. Obama had won the Hawaiian Democratic Caucus on February 19, 2008 with 76% of the vote. He was the third Hawaii-born candidate to seek the nomination of a major party and the first presidential nominee from Hawaii.[80][81]

Transportation

A system of state highways encircles each main island. Only Oʻahu has federal highways, and is the only area outside the contiguous 48 states to have signed Interstate highways. Travel can be slow due to narrow winding roads, and congested in cities. Each major island has a public bus system.

Commercial airlines provide most mainland and inter-island travel. Hawaiian Airlines, Mokulele Airlines, and go! use jets between the larger airports in Honolulu, Līhuʻe, Kahului, Kona, and Hilo, while Island Air and Pacific Wings serve smaller airports. These airlines also provide air freight service between the islands.

Norwegian Cruise Lines provides passenger cruise service between the islands. The Hawaii Superferry planned to operate between Oʻahu and other major islands. Legal issues over environmental impact statements and protests temporarily delayed it. Service to Maui started in December 2007, but shut down in March 2009.[82]-copy of wikipedia

Lakota portraits Total population 55,000 of Lakota on reservations,

Lakota portraits Total population 55,000 of Lakota on reservations,